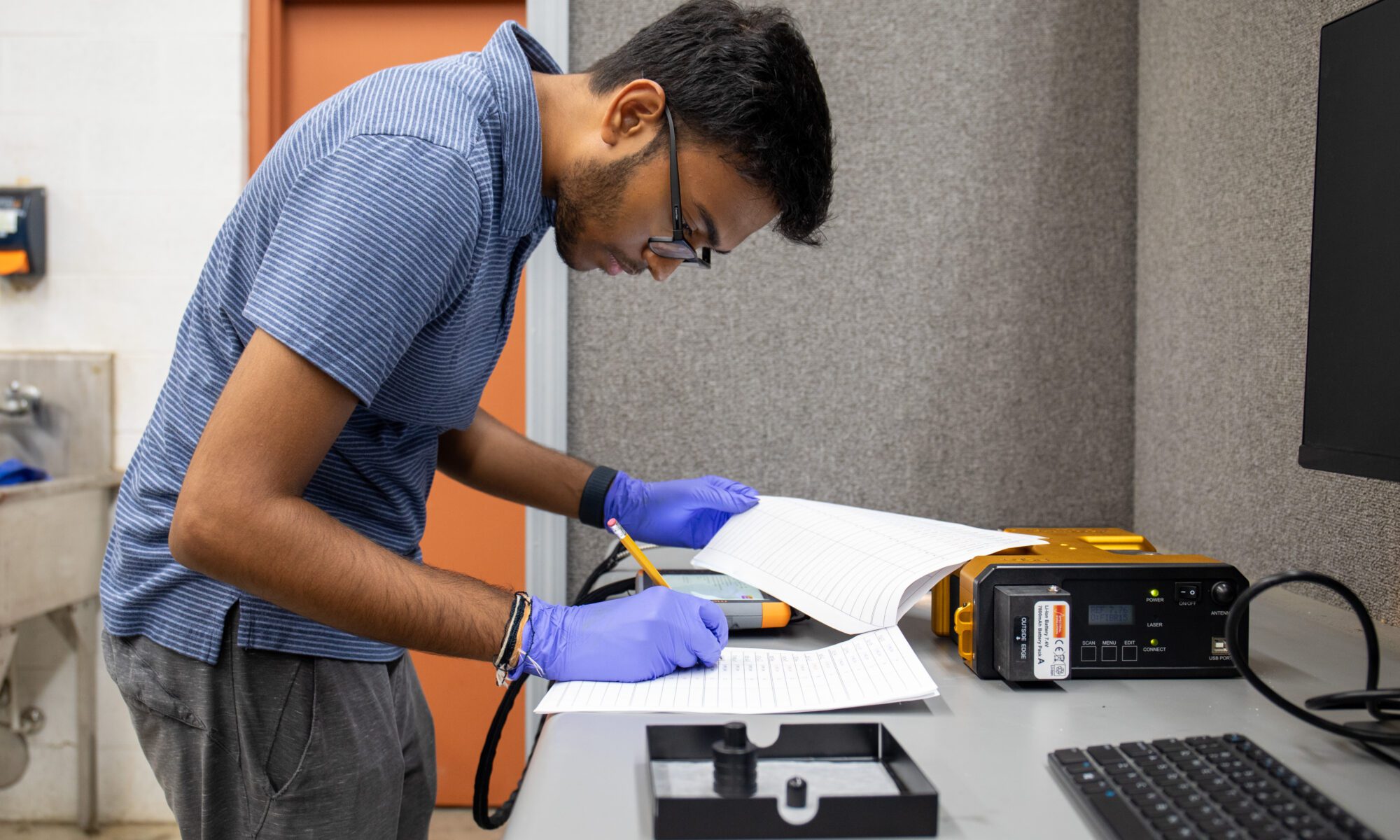

Sophomore computer science student Koushik Sanjay Saravana Kumar conducting research for Sathish Samiappan’s lab: AI-Driven Advanced Precision Technologies for Sensing (ADAPT). Photo by Celina Menard.

The Herbert College Agriculture’s Department of Biosystems of Engineering and Soil Science is taking soil science research to the next level through artificial intelligence. What’s more, students get to participate in these cutting-edge projects to enhance their educational experience.

Sathish Samiappan, associate professor in the Department of Biosystems of Engineering and Soil Science, leads two research projects combining AI with soil science: “AI modeling of microplastics in agricultural soils” and “AI modeling of soil samples from human remains.”

Such innovative research projects are bound to attract talented students from all across the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, including sophomore computer science student Koushik Sanjay Saravana Kumar.

Reading about Samiappan’s work on creating AI models for agricultural practices immediately piqued Kumar’s curiosity. “The projects like using AI for classification for microplastics and human decomposition-impacted soils were very unique and seemed like a great learning process,” says Kumar. Samiappan hired Kumar as an undergraduate research assistant in his lab for summer 2025, but continues to work on the projects today.

Smart Spotting Human Decomposition

The human remains project involved the development of an AI method to help forensic scientists quickly identify soil affected by a human cadaver decomposition (human remains), thus distinguishing it from normal soil. According to Samiappan, “current methods are slow, labor-intensive, and require lab analysis.”

Kumar used an instrument called a spectroradiometer to measure the soil’s spectral “fingerprint,” or the unique way a substance reflects light across different colors (wavelengths). The light reflected from human remains-impacted soil showed noticeably different patterns than control soil. Kumar built a specialized AI model called a 1D Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to analyze the fingerprints. The AI model classified the soil with an accuracy of 98%, demonstrating a robust, non-destructive, and much faster way to map and monitor the effects of decomposition on soil.

Kumar is working on a journal article from this research, and his abstract was accepted by the American Association of Forensic Science. He will present this research at the American Association of Forensic Science conference in New Orleans, Louisiana, in February 2026.

Harnessing AI to Detect Microplastics

The second project Kumar continues to assist on aims to create a fast, portable, and cost-effective camera system to study microplastics in farm dirt. Kumar worked on the initial part of this research, collecting high-quality pictures of the soil with varying percentages of microplastics. He then implemented an AI-based image classification model to instantly spot the microplastic bits in the photos. It is a more effective and less expensive method than standard practices.

Kumar loves the “discovery” associated with this work, and how smaller studies lead to new questions. For example, after the first round of results for the microplastics project, which they were more than satisfied with, they tried different datasets with plans to use an object detection model to detect microplastics in the future.

Changing the Game for Soil Detection

Both projects demonstrate the positive impacts of AI techniques on soil detection. In addition to being less destructive than standard methods, the Hyperspectral Spectrometry and 1D CNN technology speeds up the investigative process by providing timely monitoring and identification of cadaver decomposition islands at crime scenes. According to Samiappan, these methods are applicable to other areas of soil monitoring and health assessment.

Similarly, the camera system “enables the large-scale, rapid assessment of microplastic pollution distribution in agricultural soils,” says Samiappan. Timely and comprehensive data is critical for developing mitigation strategies and standardized protocols for microplastic pollution. Lastly, these methods show the impact of microplastics on soil health and therefore our food.

The work continues to this day, showing revolutionary ways to detect human remains and identify harmful substances in soil. And students like Kumar get to be a part of this cutting edge research, benefiting their education and future careers.

From Classroom to Career

Involving students in this type of work helps Samiappan “build preliminary research results to apply for larger federal grants.” Additionally, students like Kumar gain hands-on experience with advanced AI technology while solving real-world problems. Not to mention a strong foundation for graduate studies and research-focused careers.

Combining the disciplines of soil science and computer science through these two projects has opened Kumar up to more opportunities and possibilities post-graduation. He says, “I see this experience as a stepping stone to move forward in my career.”